December 30, 2016

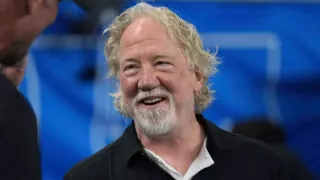

Jeremy Webb on Huntington Theatre Company's Production of 'A Doll's House'

Kilian Melloy READ TIME: 11 MIN.

Jeremy Webb returns to the Huntington Stage Company Stage after having previously appeared there as Victor in No�l Coward's "Private Lives," directed by Mariah Aitken. This time around the play is another well-regarded classic, though of a decidedly more somber hue: Henrik Ibsen's "A Doll's House," a play that's hailed in some quarter as an early feminist work but which the author himself regarded as an examination of how human beings in general can be robbed by social expectation and by the law itself of their moral agency. Long regarded as a foundational work of modern theater, "A Doll's House" has been given a fresh perspective in a contemporary translation - and adaptation - by British playwright Bryony Lavery. The Huntington's production will premiere Jan. 6 and run through Feb. 5 at the BU Theatre.

The play concerns a housewife, Nora Helmer (Andrea Syglowski, also returning to the Huntington after an Elliot Norton Award-winning turn in "Venus in Fur"), who covertly takes action to save her husband, Torvald Helmer (Sekou Laidlow), even though it means breaking the law. As a result, Nora finds herself in an increasingly untenable position thanks to a blackmailer's demands.

Webb plays Dr. Rank, a close friend of the family with problems of his own. While Nora struggles to extricate herself from a looming disaster that could devastate her family, Dr. Rank knows he is approaching the end of his life thanks to a fatal ailment he refers to as "spinal tuberculosis." The affliction, and ills social and ethical, served as focal points in an interview EDGE recently enjoyed with Webb.

EDGE: You are playing Dr. Rank, who is dying of 'spinal tuberculosis,' whatever that is. It sounds mysterious. What have you decided, in researching the character, that 'spinal tuberculosis' means?

Jeremy Webb: [In the role of Dr. Rank] I'm actually dying of acute spinal meningitis, which is caused by hereditary syphilis. In other words, my father was a philanderer and gave syphilis to my mother, either while she was pregnant with me or beforehand, so I was born with hereditary syphilis.

My research is crude because I'm not a doctor, but I've been reading a lot of Fournier, who's a French expert on syphilis who was publishing a lot in 1907, 1912. We're pushing the production forward [in time a decade or so], so what Fournier was writing becomes relevant. He writes about a form of syphilis that would have presented in a young child; I would have had rashes. Syphilis can go into the body and remain there for 20 to 35 years, and then present in this tertiary stage, this late stage, by causing spinal meningitis, or other severe health issues.

That's what he has, and it was pretty common in the society at the time for people who had syphilis to call it tuberculosis, because it wasn't as... I don't know... socially unacceptable to say [you're suffering from] tuberculosis. In this fuzziness you already see Ibsen talking to us about what is and isn't socially acceptable.

EDGE: We just assume we invented things like that, like the social stigma that used to happen around HIV in the early years of the AIDS epidemic -- and still does, to an extent.

Jeremy Webb: Right. It's not a perfect analogy, but one thing I'm thinking of a lot is how when famous people, especially in the '80s and early '90s, were dying of AIDS, you'd read in the paper that they died of pneumonia -- which technically was true, but it's not the whole story. I think there's a similarity there.

EDGE: The play is set in Norway, of course, but still it's interesting that in this production they pushed the setting up to closer to the year when American women gained the right to vote. This is a play about women, and women struggling with the status of being the property of their husbands, and being generally infantilized by their male relatives.

Jeremy Webb: That's absolutely true. I feel like Melia [Bensussen, the director] - who is brilliant, by the way - I feel that she has pushed it right up against all of those changes. We're coming close to women's rights; we're coming close, too, to penicillin, from my personal perspective. Penicillin was discovered in 1928, and by 1940 these kinds of diseases were much more manageable and much less fatal. But Melia and the designers are deeply influenced in this production by the work of Edvard Munch, the painter who painted 'The Scream.' He was working more around the turn of the century and they really wanted the production to have those intense colors, those reds, purples and oranges. So we are just leaning into history with this production.

EDGE: Have you worked with Melia Bensussen before?

Jeremy Webb: I had never met her before. I was actually in Maine in July, with my husband, who was playing Peron in 'Evita' at Maine State Music Theater. I got the call to come to New York and audition, and I was like, 'But I'm supposed to be eating lobster today!' Then I re-read the play, and I jumped on a Bolt bus from Portland to New York, to audition and then she called me back. I'm thrilled that she did, because she's up to the task. She's a really, really brilliant director.

EDGE You've performed with the Huntington in the past, when you played Victor in 'Private Lives.' Do you feel there is any sort of literary or stylistic connection between those plays?

Jeremy Webb: I guess I would say yes and no; I mean, my initial impulse was to say no, that Coward was writing to help us take a vacation from our lives for two hours, and Ibsen is writing to insist we take even a deeper and closer look at ourselves than we probably would want to. But when I think about it, I feel like that's not being fair to Coward, because he writes about the multitudes as well. I don't know -- I haven't thought about it in terms of a connection between Ibsen and Coward, to tell you the truth.

EDGE I guess I am wondering more generally about plays from earlier eras, as opposed to plays written in the last decade or so... theater has changed and evolved so much in recent decades, and older plays strike me have having a more formal structure and tone about them.

Jeremy Webb: Yeah, you know, we were discussing in rehearsal the other day the fact that George Bernard Shaw was writing many, many plays, and also writing reviews in critical response to plays that he saw. During the time when 'Doll's House' premiered, he traveled to, I think it was Amsterdam, to see a production of the play, and then saw it in its London premiere and wrote a really fascinating review. More to the point of what you're saying, we were talking about what that production must have been like -- pre-Stanislavski, pre-Chekhov, pre-modern. This play really is considered one of the first modern plays. But that being said, what must the performance style have been like in that production that Shaw saw in London in, like, 1891? The broad-strokes, gestural, indicative style of acting, all those pre-Stanislavski ideas of the way of working, versus how we approach this kind of material today. Right? Because the approach now to this kind of material is realism: Getting very specific, getting very real, establishing the details, creating character biographies. So, yeah, it's really interesting to consider what this play must have looked like when it premiered, versus the attack that a company of modern actors make upon it.

EDGE: 'A Doll's House' has an intriguing backstory in and of itself, having been based in part on things that actually happened to a married couple of Ibsen's acquaintance. But while we might think we've made a great deal of progress since the play's premiere in 1879, sexism is still a major factor in how law and society treat women.

Jeremy Webb: Absolutely. What makes the play universal, what makes it great, what makes it something that we want to explore 140-ish years after it was written, is that it's talking about universal truths. It's not ultimately talking about something as surface a particular law or particular amendment to a law, or even suffrage; but what I think the play is really getting after is how even when people love each other such true ways, and I think that Nora and Helmer have a good marriage. There is certainly lots of evidence in the text that they are still really into each other, they are still really turned on by each other; they have a good rapport, they enjoy spending time together. But ultimately, marriage is difficult, human connection is difficult, as is participation in the social structure. Participating in the world of couples getting together with couples, and husbands doing the thinking for wives, and wives taking that from husbands... it is an imposed social structure that doesn't have a lot to do with man's humanity, it doesn't have a lot to do with the humanistic point of view -- how we see ourselves; how we feel when it's just us against the world. You have this imposed social structure butting up against man's innate, universal nature, which is to take care of himself, and that's where Nora's crisis and catharsis come from.

It's not that Helmer is a horrible husband. He just has a deeper involvement, ultimately, with what his society of men ask of him. We've been talking a lot, too, about how Ibsen would be displeased that we might see it as a feminist play, although Nora is a tremendously powerful female character. But that's not actually what he was writing about.

EDGE: Ibsen did remark on that. He said he had wanted to write a play looking at the human condition -- humanity in general. This wasn't meant to be a feminist work. I wonder if it would be interesting or even possible for someone to make an experimental production in which those two married characters are both men.

Jeremy Webb: Oh, yeah; I mean, I think the same issues would prevail, right? I'm married to a man, and there are lots of us now who are. I went to watch a video of this play in a previous production on tape at Lincoln Center and all I thought about as I was watching the play was my own marriage.

[Laughter]

Ibsen really gets into the heart of that. Act III is brutal, it's just fucking brutal in that moment when [a solution to their problems arrive and] Helmer says, 'I am saved, I am saved!,' and she says, 'Don't you mean "we?"' And he says, 'Of course, we!' And in the play, the stakes are huge -- much huger than anything that has happened to me in my life, but it's that quest that I think a lot of us have in the best of marriages and relationships, where we go, 'Is it "us" or "me" against the world?'

We were talking in rehearsal the other day about it: That [hypothetical] moment when there's a fire in the house at midnight, and there's one way out, and you wake up next to your husband or wife. Do they let you go first? And then the ceiling crashes in, and they die, but they've put you first? Or in that moment do they go first, and you realize that it really was every man for himself all along? What is really at the heart of the matter? What really is the bottom line of your relationship and your connection with the person that you're in a relationship with? That's heavy stuff, and it's important stuff. It's one of the things that makes the play so brilliant. And it exactly what Helmer and Nora butt up against at the climax of this play.

EDGE: Like you say, it's a matter of looking at something universal.

Jeremy Webb: Yes, absolutely, and through the universal we all see ourselves -- if we are willing to look.

EDGE You mentioned having gotten a call about the audition, but had you reached out beforehand? Or did they call you up out of the blue because, say, they just loved you so much from your work in 'Private Lives?'

Jeremy Webb: I did not reach out. I have reached out; lots of times in my career I will make those calls, particularly to directors I've worked with before. Of course, I didn't know Melia previously. So, I did not reach out, but it was fairly straightforward the way that I worked. My manager got a call from the Huntington casting director for an audition and I went in and auditioned, and then I had a callback the next day, and then I got a call that I was cast.

I am more and more interested, I guess, as I reach this middle... [Laughter] ...or whatever stage in my work and my career, in working with people that I've worked with before, and working on texts that interest me and excite me. I played a lot of lot of boring, vanilla ing�nues in my twenties... [Laughter] ....and I did reach the point, maybe five years ago, where I just said to myself, and to my representative and my manager, 'That's enough of that!' There's a lot that I love about what I do, and there's a lot that I have yet to do, but playing boring ing�nues, who have to hold the structure of a play together with little or no payoff, is no longer on my list.

This role interests me in particular because of his - you mentioned mystery, which I think is an interesting way to describe Dr. Rank. He's referred to as 'seedy,' which I don't understand at all; he's referred to as 'sexy,' which I like; he's referred to by others as almost lascivious or salacious; I don't get that from him as much. I think the big scene with Nora in Act II is tender. I think they have a deep understanding. He's obviously been friends with Helmer for a long time. We're thinking they met in college. And he's been friends with Nora, obviously, for the last ten years; but he is certainly not sneaking around behind Helmer's back trying to steal his wife. That is certainly not what's going on in this play. I guess we have yet to specifically address exactly what is going on, but... anyway, I enjoy playing this kind of role very much, and I certainly love working at this theater.

EDGE In the back of my mind I was thinking, Aren't you a little young to play Dr. Rank? I always imagined Dr. Rank to be considerably older than Nora and Helmer, like 60 or so.

Jeremy Webb: I know Melia consciously cast the entire production young, and I think this is a brilliant impulse, particularly for classic plays, because I think that [in contrast to how we now might want to cast productions], in the 1940s and '50s and '60s, [you were apt to see] a 50-year-old Romeo. It's like that old adage about 'King Lear,' when you're old enough to play the role, you don't have the stamina for it, and when you have the stamina for it you're not the right age. Well that's great. Some actors are compelling enough to make you overlook verisimilitude in favor of sheer theatrical brilliance.

But if you really track Rank's illness, it's a stretch to believe that given what he has that he even would have lived to be my age. The idea he could have lived with hereditary syphilis to the age of 60 is nearly impossible -- I would in fact argue the opposite: All those productions where Rank is 60, there must have been a really brilliant actor and they wanted to overlook the specifics of the play, because as I drill down into the specific, and also the heartache and the tragedy at the center of this play, it is more pronounced the younger the characters are. The more life they have to lose, the more I think we end up feeling for them. I think the fact that Nora, Helmer, and I are all youngish, it certainly makes us a very potent trio, to my mind.

The Huntington Theatre Company's production of Ibsen's "A Doll's House" runs Jan. 4 - Feb. 6 at the BU Theatre. For tickets and more information, please go to http://www.huntingtontheatre.org/season/2016-2017/a-dolls-house